Superglobals are special built-in variables in PHP that are available from any function, class, or file without a previous declaration of them as global variables.

That practically means there is no need to use the global keyword to access them.

Below is how we can access a common global variable from a function:

Without the global keyword, we’d get an ‘Undefined variable‘ notice, and the result would be different (-3 instead of 7).

This code echoes -3 because uninitialized variables in PHP have a default value of null, and when you perform arithmetic operations on null values, PHP converts them to 0.

Here’s what happens step by step:

$xis declared but not assigned a value →$xisnull- When you calculate

$x - $n, PHP performs type coersion (automatic type conversion) null -3- Result:

-3

Superglobals, on the other hand, do not need the global keyword:

We’re going to be talking about how the $_SESSION superglobal works later on, but for now, just pay attention to how we get access to the global scope without the use of the global keyword.

There are nine superglobals in PHP

These superglobal variables are:

- $_GLOBALS: It holds a reference to all the global variables that have been defined in a PHP script.

- $_GET: contains the parameters passed to the script through the query string.

- $_POST: contains data sent via an HTTP POST request.

- $_COOKIE: contains data passed to the script as cookie values.

- $_SESSION: contains data stored in a user’s session.

- $_REQUEST: contains all the data sent by the user’s client.

- $_SERVER: contains information about the server.

- $_FILES: contains data of files sent via an HTTP POST file upload.

- $_ENV: contains information about the environment.

Becoming familiar with the basics of each superglobal makes data manipulation in web applications easy.

Let’s see these superglobals one by one.

The $_GLOBALS Variable in PHP

The $_GLOBALS variable is an associative array that references all variables in global scope, with the variable names being the keys to the array.

Let’s see how the $_GLOBALS variable can access a global variable with an example:

Apart from accessing global variables, $_GLOBALS can be used to modify them.

In the same example:

We can use this superglobal in order to pass variables between functions

But there is a better, less verbose, way to do the same thing with the USE keyword.

Used in an anonymous function, the USE keyword enables us to introduce variables from outer scope.

NOTE: As of PHP 8.1.0, $GLOBALS is now a read-only copy of the global symbol table. So for the post-PHP 8.1 versions of PHP, modifying global variables through their copy is not possible.

Before PHP 8.1:

Here, by modifying the copy, we modify the $_GLOBALS array as well.

From version PHP 8.1 and on:

Copy modification does not affect $_GLOBALS anymore.

The $_SERVER superglobal

The $_SERVER superglobal array makes available information about the server on which the current script is being executed. Information such as the server name, the user agent, the queryString, and other variables.

PHP automatically defines the array based on the server configuration and the current HTTP request, and therefore, there is no guarantee that every single variable will be provided.

In any case, the CGI/1.1 specification covers most of these variables, and they are likely to be defined.

Example of $_SERVER in use:

We can list all available elements with the following code:

It’s going to print, depending on our server configuration, something similar to the image below:

We are going to look at some of the most commonly used elements of the PHP $_SERVER superglobal.

A complete list is available in the PHP documentation.

$_SERVER[‘REQUEST_METHOD’]

It returns the request method that is used to access the page.

This can be a ‘POST‘, a ‘GET‘, a ‘PUT‘ method e.t.c

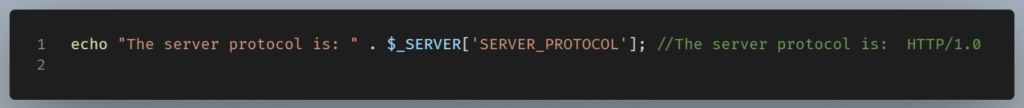

$_SERVER[‘SERVER_PROTOCOL’]

It stores the name and version of the protocol of the request, like HTTP 1, or HTTP/2 etc.

$_SERVER[‘SERVER_NAME’]

It is used in order to retrieve the name of the host server.

$_SERVER[‘SERVER_PORT’]

It returns the port number that the server machine (not the client’s machine) uses for communication.

$_SERVER[‘SERVER_SOFTWARE’]

It is used to get the server identification string that contains details of the server software.

$_SERVER[‘SERVER_ADMIN’]

It is used to store the email address of the server administrator/webmaster.

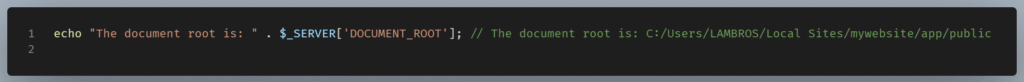

$_SERVER[‘DOCUMENT_ROOT’]

It returns the root of the document. That’s where the script that we are running lives.

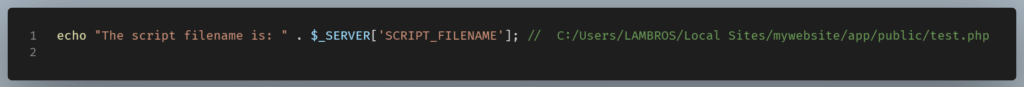

$_SERVER[‘SCRIPT_FILENAME’]

It returns not just the filename, as the name implies, but the absolute pathname of the currently executed PHP script.

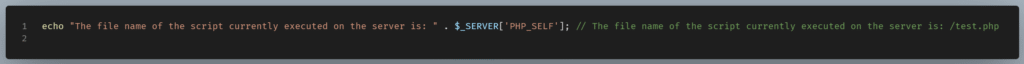

$_SERVER[‘PHP_SELF’]

Just like $_SERVER[‘SCRIPT_NAME’], it returns the filename of the script currently executed on the server.

It can include the URL query string, though.

NOTE: It is essential to perform HTML encoding on $_SERVER['PHP_SELF'] when used in the action attribute of your form tag in order to avoid cross site scripting (XSS) attacks.

$_SERVER[‘REMOTE_ADDR’]

It returns the IP address of the client.

NOTE: It gives the address of the machine where the connection is coming from, not the address of the connecting computer. Remember that in a local connection, like in the example below, both client and server have (obviously) the same address, namely 124.0.0.1, so this address is returned.

All computers universally use this address, commonly referred to as 'localhost'. There is also a second IP address, in the form of 45.139….., which is provided by an ISP and is used for communicating with other computers. Since in a local connection our computer is both the server and the client, the former address is the one returned.

$_SERVER[‘HTTP_HOST’]

It returns the HTTP host header from the current request. The HTTP host specifies the domain name the client tries to access. If a user wants to visit mywebsite.com, their client needs to make a request with the HTTP host header, as shown below:

Host: mywebsite.com and this is the value returned by the $_SERVER[‘HTTP_HOST’]

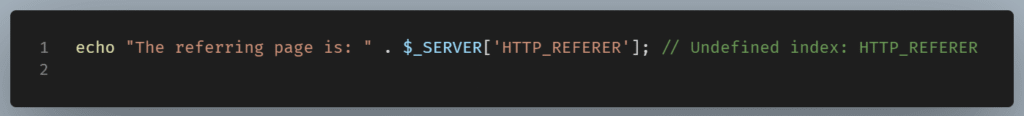

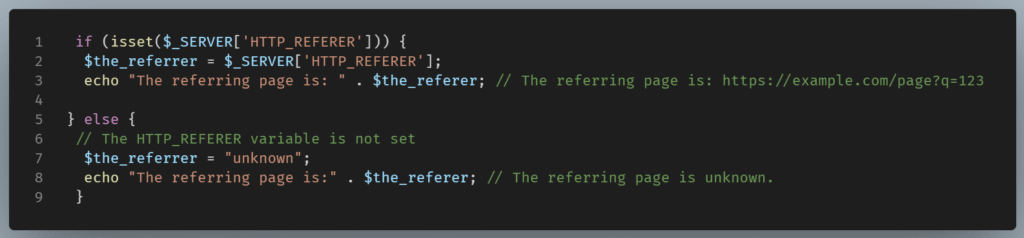

$_SERVER[‘HTTP_REFERER’]

It returns, if available, an absolute or partial address from which a resource has been requested.

It is not always available, though, since the current page could be accessed by typing the URL into the address bar or using a bookmark. In that case, there will be no referring page and $_SERVER[‘HTTP_REFERER’] will not be set.

To avoid the latter warning, we can check this element’s presence with the help of the isset() function.

$_SERVER[‘HTTP_USER_AGENT’]

It returns the user agent string, which gives information about the application type, operating system, software vendor, or software version of the requesting software user agent.

NOTE: We see in our example that although the user agent string shows we are on a Chrome browser of the 120.0.0.0 version, we also get, at the beginning of the string, a ‘Mozilla/5.0’ token. We get this regardless of the browser that we use, even if it is Chrome, Safari, Opera, or any other browser for that matter. Mozilla/5.0 is the general token that says that the browser is Mozilla-compatible, and for historical reasons, almost every browser today sends it.

$_SERVER[‘QUERY_STRING’]

It returns, if applicable, the URL query string.

If there were no query string, we would get:

The $_ENV superglobal

The $_ENV superglobal is an associative array of variables passed from the environment in which PHP is running.

These variables are called environment variables and are set by the web server or the server’s operating system. They are not PHP-specific, but system-wide and can be accessed by other programming languages as well.

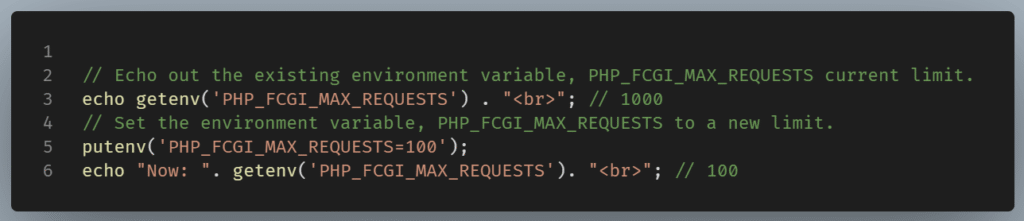

Using getenv

To retrieve an environment variable, we use the getenv() function.

If we want to get the values of all the available environment variables, we can use the following script:

We get:

NOTE: Environment variables are case sensitive on UNIX and case insensitive on Windows

For example:

Since I am on a Windows machine, I can write the environment variable PHP_FCGI_MAX_REQUESTS in lowercase characters.

That wouldn’t be the case in a Linux machine.

PHP_FCGI_MAX_REQUESTS determines how many requests a PHP job should handle before ending and restarting.

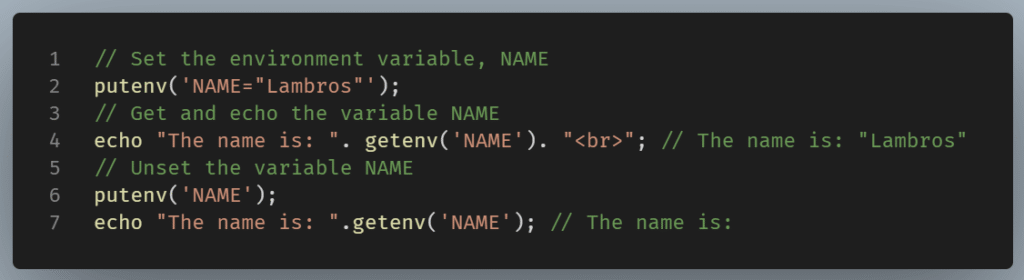

Using putenv()

By using this function, we can easily set a new environment variable for the duration of the current request.

The putenv() function can alter the value of an existing environment variable or set the value of a newly created.

Variables set with the putenv() function are only available by calling the getenv() function.

Regarding existing environment variables, we can set a new variable from scratch:

NOTE: White spaces are allowed in environment variables and must be taken into account.

‘NAME’ and ‘NAME ‘ (with a space after) are two distinct variables.

The $_GET superglobal

The $_GET superglobal is an associative array of variables. These variables are received via the HTTP GET method.

This method is one of the two ways browsers use to send information to the web server.

The other is the POST method that we are going to talk about later on.

A GET request is sent as a URL containing a query string added to its end with a question mark. This query string has name-value pairs as parameters.

These parameters are separated by ampersands.

Example:

http://www.mywebsite.com/about.php?name=”Lambros”&surname=”Hatzinikolaou”

The above query string contains two variables:

name=”Lambros” and surname=”Hatzinikolaou”

Regarding the previous example of a GET request, we would retrieve the variables name and surname:

We should avoid using GET requests for sensitive data as it can be easily viewed, cached, or bookmarked.

Escape before display with htmlentities()

GET requests can be subject to XSS, so it is good practice to escape before they are displayed on our web page.

Escaping means converting special characters in user input to HTML entities.

This conversion prevents them from being interpreted as code by the browser.

In PHP, we can use the htmlentities() built-in function to achieve this. This function converts special characters in user input into their HTML entities.

Let’s say we get user input from a form regarding a name and we store it in the $name variable.

In the example, a well-meaning user with the name of John filled his name, and we get the respective string on our browser.

But what if the user is not so benevolent?

Let’s say he puts, instead of his name, something like:

Now, when we load our page, we get an alert box with the string “This is an XSS attack”.

We can prevent this by escaping our code:

Now we get the string: "The name is <script>alert(“This is XSS attack”)</script>"

Note: The malicious code the malevolent user injected in the input is displayed as simple text. So it can’t be executed by the browser.

The $_POST superglobal

The $_POST superglobal is an associative array of variables sent via an HTTP POST request.

POST requests are not cached and cannot be bookmarked or stored in a browser’s history, thus they are suitable for sending sensitive information.

The $_POST superglobal can handle data submitted from a form using a POST request.

In the above example, we have a form that asks for an email address. After submitting the form, we use the $_POST superglobal to store the variables we receive from the HTTP POST method in the variable $email.

Then we use conditional statements to check if an email has been filled in, and if this is the case, we echo a message to the browser.

Here, similarly to the example with the GET request, we are dependent on the honesty of the user. The user can input malicious code.

It is unwise to trust external input, so we’d better escape our code.

Suppose that a user enters the following script,<script>alert (“This is XSS attack”) </script> , in the name field of our form.

This is just an alert code, but it could have a malicious script.

We need to escape our code with the htmlspecialchars function.

Now we get the malicious code displayed as text.

PHP $_FILES superglobal

An HTML Form can be used not only for collecting user input but also for files.

PHP supports file uploads natively. It can receive files from the vast majority of browsers that support the multipart/form-data enctype attribute.

Before being sent to the server, form data should be encoded. The enctype attribute defines how.

The default value is application/x-www-form-urlencoded.

This format is compatible with URLs. But if the form includes files, we need to use the multipart/form-data type of encoding.

The $_FILES superglobal is an associative array that holds information about uploaded files, such as names, sizes, and error types.

Submitting a Form with a File input

When a user submits a form that includes a file input field, the file data is sent to the server, and PHP inserts information about the uploaded file to the $_FILES array.

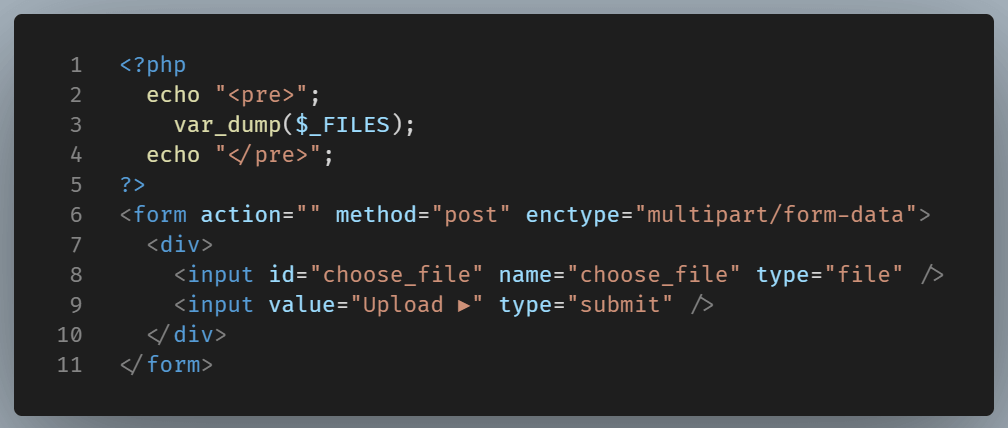

Let’s see an example:

In the above example, the enctype=”multipart/form-data” attribute enables file submission to the server via the POST method, and the input element with type=”file” enables us to use a file selection panel for finding the intended file.

In our example form, I upload the image ‘Schwab-1.jpg’ from a directory on my machine.

Looking inside the the $_FILES superglobal

We var_dump the $_FILES superglobal to look inside.

The $_FILES superglobal array structure is multidimensional, and, as we can see in the screenshot, it contains the following file data:

In the example, we see the $_FILES superglobal associative array nesting another associative array with 5 items, all representing the attributes of the file to be uploaded.

The attributes are:

name: Represents the original name of the uploaded file as it is named in the user’s machine.

type: Represents the nature and format of a document. This can be obtained from the browser but should not be completely trusted, as it can be manipulated. A better way is to use other PHP built-in functions to represent the document’s format.

tmp_name: Represents the name of the server’s temporary file in which the uploaded file will be stored.

error: Represents the [error code](link: https://www.php.net/manual/en/features.file-upload.errors.php) for this file upload with 0 meaning no error.

size: Represents the size of the uploaded file in bytes.

NOTE: I run PHP 7 on my local server, so we get six keys. But If I'd run a PHP version later to PHP 8.1 we would get one more attribute.

full_path: This key was introduced in PHP 8.1. It represents the full path as submitted by the browser. Thanks to its value, it is possible to store the relative paths or reconstruct the same directory on the server.

The full_path attribute would be there. This is something to consider since most of servers run on PHP 8+ with roughly 30% of servers running previous PHP installations.

We can access any of these attributes directly:

Handling file uploads

To handle file uploads, we use the PHP function move_uploaded_file() to move the file from the temporary directory to a location of our choice.

Here’s a simple example of handling a file upload:

In this example, the program checks if a file was uploaded successfully and then moves it to the uploads/ directory.

So far, we have talked about seven out of the nine superglobals available. We left $_Session and $_Cookie superglobals last since the mechanisms of Cookies and Sessions are quite similar and often get mixed up, which deserves a separate post.